The Sculptor Who Carved a Nation into Stone

Few artists have shaped the American landscape as literally as Gutzon Borglum. Best known for the colossal presidential faces carved into Mount Rushmore, Borglum was a man of immense ambition, vision, and complexity. His art was never merely decorative—it was nationalistic, symbolic, and engineered to endure. Through stone and steel, Borglum etched not only images but ideologies, capturing the American imagination in ways both celebrated and contested. To understand Borglum is to explore the tension between art and politics, personal ego and public identity, permanence and decay.

Early Life: Roots in Conflict and Imagination

Born in Idaho Territory in 1867 to Danish Mormon immigrants, John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum was the child of cultural and ideological collision. Raised in the American West and later educated in Europe, Borglum’s upbringing was as fractured and expansive as the land he would one day sculpt. He trained at the Académie Julian in Paris and studied under Auguste Rodin, though he later dismissed Rodin’s influence, insisting his style was “uniquely American.”These early experiences instilled in him a lifelong fascination with heroism and grandeur. According to biographer Rex Alan Smith, “Borglum believed America lacked mythic symbols carved in the permanent medium of antiquity. He set out to change that.”

Artistic Style: Realism on a Grand Scale

Borglum's style straddled the realms of neoclassicism and realism, yet what distinguished him most was scale. He favored stone over canvas and saw sculpture as a public art form meant to inspire civic pride. Borglum did not traffic in intimate expression; instead, he conjured images of leadership, patriotism, and permanence. His figures, whether carved in marble or blasted from mountains, were meant to outlast the men they represented.

“Art in America should be monumental,” Borglum once said, “not decorative.” His emphasis on grandeur reflected not just aesthetic preference, but a political idealism that echoed the Progressive Era’s hunger for national identity and myth-making.

Iconic Works: From Controversy to Immortality

While Mount Rushmore remains Borglum’s magnum opus, his earlier projects laid the groundwork for his monumental vision. In 1908, his marble bust of Abraham Lincoln was placed in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda—an honor that signaled his rising status. President Theodore Roosevelt called it “the most remarkable work of its kind in America.”

Another pivotal yet controversial commission was the Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial in Georgia. Initially contracted in 1915, the project aimed to honor Confederate leaders. Borglum's vision was vast: a high-relief carving spanning 1.5 acres. But creative clashes and political tensions—Borglum was associated with the Ku Klux Klan during this period—led to his dismissal. The incomplete work remains a reminder of both his ambitions and contradictions.

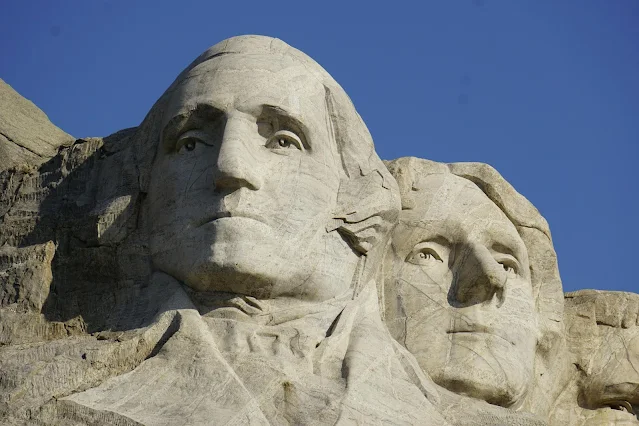

It was Mount Rushmore, however, that fused his talents with a cause palatable to broader America. Commissioned in the 1920s, Borglum chose four presidents—Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Roosevelt—intending to enshrine “the founding, expansion, preservation, and unification of the United States.” The scale was breathtaking: each head stands 60 feet tall, carved directly into South Dakota’s granite cliffs. The project continued even after his death in 1941, completed under the guidance of his son, Lincoln Borglum.

Legacy: Visionary or Megalomaniac?

Gutzon Borglum remains one of the most polarizing figures in American art history. His technical mastery and audacious scale inspired countless sculptors and public artists. Yet his associations with nativist politics, authoritarian symbolism, and questionable ethics have complicated his legacy.

Some see Borglum as a visionary who brought American ideals into permanent form; others view him as an artist whose ego matched the mountains he chiseled. In recent years, scholars and activists have scrutinized his involvement with white nationalist ideologies, particularly his time with the Stone Mountain project.

Still, Borglum’s artistic impact is undeniable. His works continue to attract millions of visitors annually. Museums and institutions across the U.S. have exhibited his lesser-known bronzes and preparatory sketches, offering a more nuanced view of his oeuvre.

Auction houses, too, have kept his legacy alive. In 2021, a bronze bust of Lincoln by Borglum fetched over $200,000 at Christie’s—testament to his lasting appeal in the art market.

Conclusion: A National Dialogue in Stone

To engage with the work of Gutzon Borglum is to grapple with the contradictions of American identity. His monuments invite awe while prompting critical reflection. They are, by design, inescapable—towering reminders of a nation’s self-image at specific moments in history.

In a time when public monuments are increasingly questioned, Borglum’s legacy asks: What do we choose to immortalize? And at what cost?

As the sun sets behind the granite faces of Mount Rushmore, casting long shadows across the Black Hills, it becomes clear that Borglum didn’t just sculpt a mountain—he carved a conversation that still echoes across America. Exploring his work is not just an art historical journey, but a civic one.

Keywords:

Gutzon Borglum biography, Mount Rushmore sculptor, American monumental art, Stone Mountain memorial, Borglum Lincoln bust, history of public art, famous American sculptors, Borglum legacy, sculpture and politics, early 20th century American art

Comments

Post a Comment